| Value | Becomes |

| `undefined` | `NaN` |

| `null` | 0 |

| `true and false` | `1` and `0` |

| `string` | `Empty string is 0, then convert the string to number, if any non-digit character are present results in NaN` |

Hence, you see that `null == 0` is false, because the type conversion from `null` to 0 isn't carried out. The equality check for `undefined` and `null` is defined such that without any conversion, they are equal to each other only and equal to nothing else!

When `undefined` is used together with numbers for comparison operator, it will always be false. This is because `undefined` gets converted to `NaN`. And equality check don't work because like mentioned previously `undefined` only equal to `null` and nothing else. ### Takeaway - If you are going to compare a variable that might be `undefined/null` treat it with care - Don't use `>=, >, <, <=` if the variable might be `undefined/null` have a separate check to deal with those values. [https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Equality\_comparisons\_and\_sameness](https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Equality_comparisons_and_sameness) A nice read up on how the comparison is actually done, if needed for further clarification. # Conditional and Logical Operator ### Ternary Operator ```javascript let accessAllowed; if (age > 18) { accessedAllowed = true; } else { accessedAllowed = false; } // Can be simplified into just accessedAllowed = age > 18 ? true : false; ``` ### || (OR) Returns true if one of the boolean value is true. There is an "extra" feature of JavaScript for the OR operator. ```javascript result = value1 || value2 || value3; ``` Given the above code snippet, the OR operator will go from left to right evaluating each expressions, and for each value it will convert it into a boolean, if the result is `true` it will stop and return the original value of that expression. if all of the expressions has been evaluated, and all of them are `false` then return the last value. Return the first truthy value or the last one if none were found. ```javascript let firstName = ""; let lastName = ""; let nickName = "SuperCoder"; alert( firstName || lastName || nickName || "Anonymous"); // SuperCoder ``` ### && (AND) Return true only if both operand are true. Just like OR there is also this "extra" feature from JavaScript for AND operator. ``` result = value1 && value2 && value3; ``` It will evaluate left to right as well. It will convert each value to a boolean, if the result is `false` then it will stop and return the original value. If all of the values are evaluated and are all `true`, then return the last value. Return the first falsey value or the last one if none were found. ```javascript alert( 1 && 0 ); // 0 alert( 1 && 5 ); // 5 ``` ### ! (NOT) It first convert the operand to a boolean type, then return the inverse of that value. ```javascript result = !value; ``` Double NOT can be used to convert value to boolean conversion. ### Nullish coalescing ?? A value is defined when it's neither `null` or `undefined`. The result of `a ?? b` is - if `a` is defined, then `a` - if `a` isn't defined, then `b` Basically the `??` operator will return the first argument if it's not `null/undefined`, otherwise, the second one. This is just a shorter syntax for writing ```javascript result = (a !== null && a !== undefined) ? a : b; // Is the same as result = a ?? b; ``` You can also use `??` to pick the first value that isn't `null/undefined`. As opposed to `||`, it returns the first truthy value! This results in a subtle difference: ```javascript let height = 0; alert(height || 100); // 100 alert(height ?? 100); // 0 ``` We might only want to use a default value (in this case is 100), when the variable is `null/undefined`. However, if you use `||` you will be picking the first truthy value, and since `0` is considered falsey you will be skipping the default value, as opposed to the `??` operator, which does what we want. Only use the 100 default value, if it is `null/undefined`. # Loops and switch statement ### While and for loop They are the same as in Python, C, and Java ```javascript while (condition) { // Repeat certain code } for (begin; condition; step) { // Repeat certain code } ``` `break and continue` both works the same way as in any other language. ### Switch statement ```javascript switch(x) { case 'value1': // Do something if x is === 'value1' break; case 'value2': // Do something if x is === 'value2' break; default: // Do something if x isn't equal to any value above break; } ``` The equality for the case is checked using strict equality (===). # Functions, function expression, arrow function ### Function Declaration To declare a function follow the syntax: ```javascript function function_name(parameter1, parameter2, ..., parameterN) { // Body of the function } ``` The function can have access to outer variable, as well as modifying it. The outer variable is only used if there is no local one, if there is a same-named variable that is declared inside the function then it shadows the outer one. The outer one is ignored. JavaScript's function parameter are passed by value, meaning a copy of the argument is copied into the parameter. ##### Default values If you call a function without providing the arguments required, then the corresponding value for those parameters becomes `undefined`. You can provide default values in the function declaration if the argument is not passed for that parameter then it will use the default values. It is also used if the argument is specified but is equal to `undefined`. ```javascript function foo(from, text="hello world") { console.log(from + ": " + text); } ``` Call `foo("Ann")` will result in `"Ann: hello world"` Call `foo("Ann", undefined)` will also result in `"Ann: hello world"` ##### Return Value A function without `return` or without returning a explicit value returns `undefined`, just like how Python returns `None`. ### Function expressions Another way of creating a function is via function expressions. It let you create a new function in the middle of any expression: ```javascript let foo = function() { console.log("foo!"); }; foo(); // Print out foo! ``` The function creation occurs in the middle of a assignment expression thus it is a function expression! Function expression should have a semicolon at the end because it is an assignment statement, which is good practice.Functions in JavaScript are higher order, meaning that you can pass a function as an argument and return a function as a return value.

##### Anonymous functions If you just write a function expression without storing it into a variable, then that is an anonymous function. It is only accessible to the context that it is passed into, and not anywhere else. ```javascript function run_callback(callback) { callback(); } run_callback(function() {console.log("hi im callback!")}); ``` ### Function declaration vs function expression A function expression is created when the execution reaches it and is usable only from that moment and onward. On the other hand, a function declaration can be called earlier than it is defined, and it will still work. ```javascript foo(); // fooing! function foo() { console.log("fooing!"); } ``` Global function declaration is visible in the entire script, no matter where it is. ```javascript foo(); // error let foo = function() { console.log("fooing!"); } ``` However, function expression are created when execution reaches them, which means line number 1 wouldn't know what foo is at that point. ### Arrow function A much more concise way of creating a function compared to function expression is via arrow functions. Here is how one looks in function expression vs arrow function: ```javascript let func = (arg1, arg2, ..., argN) => expression; ``` This arrow function accepts `n` arguments and then evaluates the `expression` on the right side and then return the result. ```javascript let func = function(arg1, arg2) { return arg1 + arg2; } let func = (arg1, arg2) => arg1 + arg2; ``` In this case, both `func` does the same thing, but the arrow function on line 5 is much more concise in that it will evaluate `arg1 + arg2` and then returns it without you having to specify a return. ##### One argument If the arrow function you are writing only have one argument then you can skip the parentheses around the parameter. But having it makes it much more readable. ```javascript let double = n => n * 2; ``` ##### No argument If the function takes no argument, the empty parentheses must be present. ```javascript let foo = () => console.log("fooing!"); ``` ##### Function expression & arrow function You can use them the same way, for example, to create anonymous callback functions: ```javascript function do_callback(callback) { callback(); } do_callback(() => { console.log("doing callback") }); // Using arrow function do_callback(function() { console.log("doing callback") }); // using function expression ``` ##### Multi-line arrow functions If your arrow function's logic is longer than one line, then you can use multi-line arrow functions: ```javascript let sum = (a, b) => { let result = a + b; return result; } ``` This is still a arrow function but you can do multiple lines now. However, by adding brackets to denote multi-line arrow function you now must provide an explicit return statement. Otherwise, the arrow function will just return `undefined` just like a regular function. Unless you don't need the multi-line arrow function to return a value, then you wouldn't need the `return` statement. # Objects and object references ### Objects In JavaScript objects are used to store key to value pair collection of data. You can think of them as dictionary in Python. You can create an object using brackets { }, and a list of optional properties that the object will have. For example: ```javascript let exampleObj = { age: 30, name: "John" }; ``` Access/modify the property using dot notation: ```javascript console.log(exampleObj.age); exampleObj.age = 50; ``` To delete a property you can use the `delete` operator ```javascript delete exampleObj.age; ``` You can also create property that is multi-worded, but they must be quoted: ```javascript let exampleObj = { name: "John", age: 30, "have computer": true }; ``` Accessing multi-worded must use the square bracket notation, since dot notation require key to be a valid variable identifier (which excludes space, digit or special characters). Single word property you can either use square bracket notation or dot notation, is up to you. ```javascript console.log(exampleObj["have computer"]); ``` ##### Empty Object You can create empty object using either of these syntax: ```javascript let user = new Object(); let user = {}; ``` ##### Accessing object property With the square bracket notation, you can use a variable to query the property. However, you cannot do the same with dot notation, it doesn't work. ```javascript let key = "name"; console.log(exampleObj[key]); // Print out John console.log(example.key); // Undefined, because it tries to find property named key ``` ##### Computed properties To insert a property name that is from a variable you can use the square bracket. ```javascript let fruit = prompt("What fruit do you want?"); let bag = { [fruit]: 5 } console.log(bag.apple); ``` In this case, if the user entered "apple", then the apple property will be inserted into the `bag` object with value of 5. ##### Property value shorthand If the variable you are assigning a property attribute to is the same as the property name, like below: ```javascript function makeUser(name, age) { return { name: name, age: age } } ``` You can just ignore writing the property assignment part and just put the variable name like below: ```javascript function makeUser(name, age) { return { name, age } } ``` They are both equivalent, but it is a shorthand way of writing the other. If the property name is the same as the variable, then you can just use the variable name as a shorthand. You can mix and match property shorthand with normal property assignment. ##### Property name limitations Variables cannot have keyword names. However it is not true for object property, the name can be whatever even keywords! ```bash let obj = { for: 1, let: 2, return: 3 } ``` If you use other types as property name such as `0`, they are automatically converted into String so `"0"`. ```javascript let obj = { 0: "test" }; console.log(obj["0"]); console.log(obj[0]); // Print out same thing. The 0 in both the property and the square bracket are converted to String. ``` ##### Property existence test You can test if an object has a property via two ways: ```javascript console.log(user.noSuchProperty === undefined); // If this is true, then it has no "noSuchProperty" "key" in object // If this is true, it exists, false it doesn't ``` The `in` operator is more preferred, because there are cases where comparing to `undefined` will fail, for example, if the property's value is `undefined`. ### Looping over keys of object ```javascript for (let key in object) { // Executes the body for each "key" // Access the value via object[key] } ``` ##### Object.keys, values, entries These method provide a generic way of looping over an object. They are called on the `Object` class because it is meant to be generic, the each individual object can write their own while still having this generic way. - `Object.keys(obj)`: Returns an array of keys - `Object.values(obj)`: Returns an array of values - `Object.entries(obj)`: Returns an array of `[key, value]` pairs Since `Object` lack `map`, `filter`, and other functions that array supports you can simulate it using `Object.entries` follow by `Object.fromEntries` ```javascript let prices = { banana: 1, orange: 2, meat: 4, }; let doublePrice = Object.fromEntries( Object.entries(prices).map(entry => [entry[0], entry[1] * 2]) ); ``` ### Object references When you assign a primitive data type to another variable, it makes a new copy of the original value. However, if you assign another variable an existing object you are making an alias, it is a reference to the original object. It does not make a new copy. So if you change the attribute of the alias, it will also change the original object! ##### Reference comparsion Two objects are equal if they are the same object ```javascript let a = {}; let b = a; // Making a reference of a a == b; // This is true, because they are referencing the same object a === b; // Also true. ``` ##### Duplicating object The function `Object.assign(dest, ...sources)` will take in a target object, in which to copy all the property to. One or more list of source object whose's property to copy into `dest`. ```javascript let user = { name: "John" }; let perm1 = { canView: true }; let perm2 = { canEdit: true }; Object.assign(user, perm1, perm2); console.log(user); // Print out "John", true, true ``` However, `Object.assign()` doesn't support deep cloning, if the object we are copying contain another object, then it will be copying the references to the destination object. In order to do deep cloning you will have to use `structuredClone(object)` function to clone all nested objects. ```javascript let user = { name: "John", sizes: { height: 182, width: 50 } }; let clone = structuredClone(user); user.sizes == clone.sizes // false, the size object within user object is cloned as well. ``` ### Method and "this" keyword You are able to add methods (functions that is a property of an object) to the object. ```javascript let user = { name: "John", age: 30 }; // First way of adding method user.sayHi = function() { console.log(`Hi my name is ${this.name}`); }; // Second way of adding method let ricky = { name: "Ricky", age: 22, sayHi: function() { console.log(`Hi my name is ${this.name}`); } }; ``` A shorthand way of writing method for an object is you can skip out the property name: ```javascript // Second way of adding method let ricky = { name: "Ricky", age: 22, sayHi() { console.log(`Hi my name is ${this.name}`); } }; ``` The `sayHi()` function in both `ricky` object are kind of similar but not fully identical, but the shorter syntax is preferred. The `this` keyword is used to access the object that the method is invoked upon. Using `this` keyword allow you to access the object's property that it is invoked upon. In the previous example it is used to accessed `ricky`'s name property. ##### "this" is not bound Unlike other languages like Java or Python, the `this` keyword can be used in any function actually and doesn't have to be for a method. You can directly write the following function: ```javascript function sayHi() { console.log(this.name); } ``` Then you can assign it to be an object's method: ```javascript let user = {name: "John"}; let admin = {name: "Admin"}; function sayHi() { console.log("Hi I am " + this.name); } user.f = sayHi; admin.f = sayHi; user.f(); // Will say "Hi I am John". this == user admin.f(); // Will say "Hi I am Admin". this == admin ``` `this` will determine which object it is invoked upon at call-time, which object is before the dot basically.Calling the same function without an object will make `this == undefined`. If you call sayHi() directly, in the previous example then `this` will be `undefined`. If you do this in browser, then `this` will be assigned the global object `window`. In Nodejs it will also be a global object. It is expected that you call the function in an object context if it is using `this`.

### Arrow function have no "this" If you reference `this` in arrow function, then it inherit the `this` from the outer "normal" function. ```javascript let ricky = { name: "Ricky", age: 22, sayHi: function() { console.log(`Hi my name is ${this.name}`); }, foo() { let bar = (x, y) => { console.log(this); } bar(); } }; ``` In this case if you invoke `ricky.foo()` then the `this` that is being used in the `bar` arrow function will be referring to `ricky` object, since it is inheriting it from the `foo` normal function. In addition, if you invoke an arrow function that uses "this" directly without it being nested inside any function at all, "this" will be an empty object. ### Object to primitive conversion JavaScript doesn't allow you to customize how operator work on objects. Languages like Ruby, C++, or Python allows you but not JavaScript! When you are using operator with +, -, \* with objects, those objects are first converted into primitive before carrying out the operations. So the rules for converting object to primitive is as follows 1. Treating object as a boolean is always true. All objects are `true` in boolean context 2. Using object in numerical context, the behavior can be implemented by overwriting the special method 3. For object in string context, the behavior can also be implemented by overwriting the special method ##### Hints To decide which conversion that JavaScript apply to the object, hints are provided. There are total of three hints. 1. "string" This hint is provided when doing object to string conversion. 2. "number" This hint is provided when doing object to number conversion. 3. "default" This hint is provided when operator is unsure what type to expect, for example the binary `plus` operator can work both on string and number, so if a binary plus operator encounters an object, the "default" hint is provided.In addition, the `==` operator also uses the "default" hint.

##### JavaScript conversion 1. If `obj[Symbol.toPrimitive](hint)` method exists with the symbol key `Symbol.toPrimitive`(system symbol), then it is called 2. Otherwise, if the method doesn't exist and the hint is `"string"` `obj.toString()` or `obj.valueOf()` is called whichever exists 3. Otherwise, if the method doesn't exist and the hint is `"number"` `obj.valueOf()` or `obj.toString()` is called whichever exists ##### Symbol.toPrimitive If the object have this key to function property then this method is used and rest of the conversion method are ignored. ```javascript let obj = { name: "John" }; obj[Symbol.toPrimitive] = function(hint) { // Here the code to convert this object to a primitive // It MUST return a primitive value! // hint can be either "string", "number", "default" } ``` ##### toString/valueOf If there is no `Symbol.toPrimitive` then JavaScript will call `toString` and `valueOf`. - For `"string"` hint `toString` method is called, if it doesnt' exist or it returns an object instead of primitive, then `valueOf` is called - For other hints `valueOf` method is called, and again if it doesn't exist or it returns an object instead of primitive, then `toString` is calledBy default, `toString` returns a String "\[object Object\]" By default, `valueOf` returns the object itself

```javascript let user = {name: "John"}; "hello".concat(user) // hello[object Object] user.valueOf() === user // True ``` If you only implement `toString()` then it is sort of like a catch all case to handle all primitive conversion. You can't just implement `valueof()` to handle all primitive conversion since `toString()` return a primitive String by default already. # Garbage collection ### Reachability In JavaScript garbage collection is implemented through something called reachability. Variable that are reachable are kept in memory and not deleted by the garbage collector. A value is considered to be reachable if it's reachable from a root by a reference or by a chain of references. However, if an object is not reachable anymore, then it will be deleted by the garbage collector. ##### Example ```javascript let user = { name: "John" }; ``` Let's say we have this global variable `user` referencing to the object `{name: "John"}`. If `user = null;` then the reference to "John" is deleted, thus the object "John" becomes unreachable. It will be garbage collected. ##### Example ```javascript let user = { name: "John" }; let admin = user; ``` Here, we have two references that points to the "John" object. If `user = null;` the garbage collector will not delete "John" because it is still reachable via `admin`. # Constructor and "new" operator ### Constructor function Function that is meant to be a constructor are named with capital letter first and be executed with the `new` operator. We use a constructor because it creates a shorter and simpler syntax compared to creating object with `{...}` every time. ```javascript function User(name) { this.name = name; this.isAdmin = false; } // Invoking constructor let user = new User("Ricky"); console.log(user.name); // Ricky console.log(user.isAdmin); // false ``` When a function is executed with the `new` operator here it what happens 1. A new empty object is created and assigned to `this` implicitly 2. The function body executes, usually modifying `this` by adding new properties or method to it 3. Then the value of `this` is returned implicitly So step 1 and step 3 is done implicitly for you already, you just need to worry about modifying `this`. ##### new function() {...} Using this syntax you can create a single complex object that you don't aim to create again in the future. The constructor isn't saved anywhere. ```javascript let user = new function() { this.name = "John" this.isAdmin = false; }; ``` The constructor function is created and immediately called with the `new` operator. ##### Returning from constructor Normally, a constructor function don't have a return statement. But if there is one the rule are as follows: 1. If `return` is called with an object, then the object is returned instead of `this` 2. If `return` is called with a primitive, it's ignored ##### Methods in constructor You can add method in a constructor function as well, the same way you would add a property! ```javascript function User(name) { this.name = name; this.foo = function() { console.log(`My name is ` + this.name); }; } ``` You are able to write arrow functions and refer to `this` in constructor function as the `this` is bounded to the constructor's `this`. ```javascript function User(name) { this.name = name; this.foo = () => { console.log(this.name); }; this.bar = function() { console.log(this.name); } } let u1 = new User("Ricky"); u1.foo(); // Ricky u1.bar(); // Ricky ``` # Optional chaining ### Optional chaining There is this problem that if the object that you are accessing might or might not contain an object attribute say `address` and you can trying to access `address`'s attribute further say `user.address.street`, then your JavaScript will crash because it is trying to access an `undefined`'s attribute. ```javascript // The problem let user = {}; user.address.street // Error ``` To solve this we have an operator called `optional chaining`, the `?.` operator. So essentially, you replace the dot notation with `?.` and it will stop the evaluation if the value before `?.` is `undefined/null` and finally returns `undefined`. ```javascript value?.prop // Will be equal to value.prop if value exists // Otherwise if value is undefined/null it will return undefined. ``` This is a much safer way of accessing attributes that you know will be undefined. ##### Don't overuse optional chaining You should only use the optional chaining operator only when it's ok that something doesn't exist In addition, the variable that you call optional chaining on must be declared otherwise, it will be an error. ```javascript user?.address // If there is not let user; then it will be an error ``` # Symbol Type ### Symbols In JavaScript there is two primitive types that can be used as object property key 1. String 2. Symbol type Don't confuse the symbol type in Ruby with JavaScript they are different albeit similar in that they are used to create unique identifier. A symbol can be created using `Symbol()` ```javascript let id = Symbol(); ``` You can give a symbol a description as it's parameter, mostly useful for debugging purposes. ```javascript // id is a symbol with description "this is id" let id = Symbol("this is id"); ``` Symbols are guaranteed to be unique, even if they have the same description, they are considered to be different values. ```javascript let id1 = Symbol("id"); let id2 = Symbol("id"); id1 == id2 // False ``` ##### Property of symbols - Symbols don't support implicit conversion to a String. ##### Hidden properties Symbols allows you to create hidden properties on an object that no other part of code can accidentally access or overwrite ```javascript let user = { name: "John" }; let id = Symbol("id"); user[id] = 1; console.log(user[id]); ``` Here we are creating a hidden property using the id symbol that we have created. We can access it using the same symbol as the key. However, if we tried to access it using String for example `user["id"]` we would get `undefined`. Using symbol is to avoid conflict between say a third party code that wants to inject some of their own property into the object. If they are just using String key then it will likely overwrite some of the existing property for the object. However, if they use Symbols then there will be no conflicts between the identifiers. ##### Symbols... more - You can use symbols in object literal, just use the square bracket when you are using symbols as key, like how you would use an variable as key - Symbols are skipped in `for ... in` loops ### Global symbols If you want different named symbols to be referring to the same entity you can do that using global symbol registry. Create symbol in it and access them later, repeated access by the same name will return the same symbol. The function `Symbol.for(key)` will look in the global registry for a key named `key` and return the Symbol that the `key` is mapped to. If it doesn't exist it will create one. Subsequent access to the same `key` will guaranteed to return the same Symbol. ```javascript let id = Symbol.for("id"); // read from global registry, create if it doesn't exist let idAgain = Symbol.for("id"); // read it again in another part of code id == idAgain // true ``` This symbol is the same symbol in Ruby. ##### Symbol.keyFor If you want to find the `key` for a particular symbol using the Symbol object, you can do that with this function. ```javascript let globalSym1 = Symbol.for("name"); let globalSym2 = Symbol.for("name"); Symbol.keyFor(globalSym1); // "name" Symbol.keyFor(globalSym2); // "name" ``` # Arrays and methods ### Array Two ways of creating empty array ```javascript let arr = new Array(); let arr = []; ``` Create an array with elements in them ```javascript let arr = ["Apple", "Orange", "Plum"]; ``` Array in JavaScript is heterogeneous, you can store element of any type in them.`arr.length` property to get the number of element in array if you used it properly. Otherwise, if you insert item into an array with a huge gap like below

```javascript let arr = []; arr[999] = 59; console.log(arr.length); // 1000, it is the index of the last element + 1 ``` ##### arr.at() Normally, if you index an array you can only use positive indexing, i.e. `[0..length - 1]`. You can use negative index with the `arr.at` method. ##### pop/push Use `pop` to remove element from the end of the array Use `push` to insert element to the end of the array. You can insert multiple items by providing them in the parameter. Treat array as a stack, first in last out data structure. ##### shift/unshift Use `shift` to dequeue the first element from the head of the array Use `unshift` to add element to the head of the array. These two operations are slow takes `O(n)` because it requires shifting the array after removing or adding the element. ##### Queue To use an array as a queue, use the `push` and `shift` function to dequeue and enqueue element into the queue. ### Looping over array You can use a traditional index loop ```javascript let arr = ["Apple", "Orange", "Pear"]; for (let i = 0; i < arr.length; i++) { console.log(arr[i]); } ``` But if you only need to loop over the element without the indices then there is a shorter syntax ```javascript let fruits = ["Apple", "Orange", "Plum"]; // iterates over array elements for (let fruit of fruits) { console.log(fruit); } ```Remember although you can use `for ... in` loop for array, it is not optimized for looping over array, so it will be slower. In addition, you will be looping over extra properties that is in array. So it is not recommended to use `for ... in` for array iterations, only for object property iterations.

### toString() Array object implements the `toString()` method to return a comma separated value of String ```javascript let arr = [1, 2, 3]; arr.toString() // returns "1,2,3" ``` Array object doesn't have `Symbol.toPrimitive` nor a valid `valueOf`, so they only implement `toString` as a catch all object to primitive conversion. `[]` will become `""` `[1]` will become `"1"` `[1, 2]` will become `"1,2"` ### Comparison of array using == Remember that `==` comparison does type conversion if the type are different, and with objects it will be converted to a primitive, and in this case because array only implemented `toString()` it will be converted to a String. Which results in some really interesting comparison. With `==` if you are comparing two object, it will only be `true` if they are referencing the same object. The only exception is `null == undefined` is `true` and nothing else. ```javascript [] == [] // false, because they are different object when you created an empty array [0] == [0] // false, again different object ``` ```javascript 0 == [] // true, because the empty array gets converted to '', and '' is converted to 0 which is true '0' == [] // false, since empty array converts to '', those two strings are different ```So how do we actually compare array? Use a loop to compare item-by-item

### Array methods ##### arr.splice ```javascript arr.splice(start[, deleteCount, ele1, ..., elemN]) ``` The splice method will modify `arr` starting from index `start`, it removes `deleteCount` elements and then inserts `elem1, ..., elemN` at their place. Returns the array of removed elements. ```javascript let arr = ["Dusk blade", "Eclipse", "Radiant virtue", "Moonstone"]; console.log(arr.splice(1, 2)); // Prints out ["Eclipse", "Radiant virtue"] they are removed console.log(arr); // Prints out ["Dusk blade", "Moonstone"] ``` ##### arr.slice ```javascript arr.slice([start], [end]) ``` The slice method will return a new array copying all the item from index `start` to `end` not including `end`. ##### arr.concat ``` arr.concat(arg1, arg2...) ``` Create a new array that includes values from other arrays and additional items. `args` can be either an array, in which it will include every items, or it can be elements themselves which will also be appended into the array ##### indexOf, includes - `arr.indexOf(item, from)`: Looks for `item` starting from index `from`, and return the index where it is found, if it cannot find it return `-1` - `arr.includes(item, from)`: Looks for `item` starting from index `from`, and return `true` if found The comparison for `indexOf` and `includes` uses `===` strict equality checking. So if you are looking for let's say `false`, you won't be accidentally finding `0`, since `==` equality checking does type conversion. ##### arr.find If we are looking for an object with specific condition, we can use `arr.find`. This is very similar to `find` in Ruby as well. We will pass in an anonymous function into `find`, and it will find the first element that satisfy the condition, i.e. that returns `true`. When you are writing the anonymous function, if you don't need all of the arguments, it is okay to write your anonymous function without it. Since if the `find` will pass all three of those parameter into the anonymous function, but if your function doesn't take it it is okay. ```javascript function foo(a, b) { console.log(a, b); } foo(1, 2, 3); // Calling it with more argument won't matter. Extra arg are ignored foo(1); // Calling it with less arg is fine too, rest will just be undefined ``` Example of using `arr.find`: ```javascript let result = arr.find(function(item, index, array) { // if true is returned, item is returned and iteration is stopped // if no true is return, undefined is returned }); ``` There are other variant to find `arr.findIndex` if you are interested in finding the index of the element you are looking for instead of the element. `arr.findLastIndex` to search right to left. ##### arr.filter Very similar syntax to `arr.find`, but instead of searching for only one element, this method will look for all element that satisfies the condition, i.e. that returns `true` and return the result in an array. ##### arr.map Again very similar syntax as well to `find` and `map`, this time you are transforming each element of the array into something else. The function will be responsible for collecting all of the element. You just need to return the element after it is transformed ```javascript let nums = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];// Using multi-line arrow function, to practice returning.console.log(nums.map((ele) => { let result = ele * 2; return result;})); ``` ##### arr.sort Sorts the array in place. However, by default if you don't provide a comparer function it will be sorting it lexicographically, even if the elements are other type. It will attempt to convert the type into String and then sort it accordingly. ```javascript let numArr = [1, 2, 15]; numArr.sort(); // This will modify numArr to be [1, 15, 2]! Because lexicographically 2 comes after 15! ``` In order to fix this we will have to write our own comparer function. ```javascript function compareNumeric(a, b) { if (a > b) return 1; // a comes after b if (a == b) return 0; // they are equal return 0 return -1; // a comes before b } let numArr = [1, 2, 15]; numArr.sort(compareNumeric); // now this will modify numArr to be [1, 2, 15]; ``` Actually, you can even simplify this even further by just writing ```javascript arr.sort((a, b) => a - b); // Ascending arr.sort((a, b) => -(a - b)); // Descending ``` ##### arr.reverse Just reverse the order of elements in place. ```javascript let arr = [1, 10, 4, 2]; arr.reverse(); // arr is now [2, 4, 10, 1]; ``` ##### split and join Works just like how it work in Python, but with a minor differences. ```javascript let names = "Ricky Xin Rek'sai" let arr = names.split(' '); // arr is ["Ricky", "Xin", "Rek'sai"] ``` `split()` need you to specify a space `' '` if your delimiter separating the different words by a space. In addition, if you provide in an empty String `''` as delimiter, it will split the String into array of single letters. `join()` requires you to call it on the array that you are joining together, and you provide the String to join all the element together by as a parameter ```javascript let strs = ["Ricky", "Xin", "Rek'sai"]; let out = strs.join("-"); // Becomes "Ricky-Xin-Rek'sai" ``` ##### reduce/reduceRight The basic syntax for using `reduce/reduceRight` is as follows: ```javascript let value = arr.reduce(function(accumulator, item, index, array), initial); ``` - `accumulator`: The result of previous function call, on the first element it is equal to `initial` if it is provided - `item`: The current array item - `index`: The current array item's index - `array:` The array that you call `reduce` on - `initial`: if the initial is provided then `accumulator` will be assigned that value and start the iteration at the first element. **Otherwise, if `initial` is not provided, then `accumulator` will take the value of the first element of the array and start the iteration at the 2nd element** How `reduce` work is that the function will be applied to every element, the function will return a result, and that result is passed to the next element as `accumulator`. The first parameter basically becomes the storage area for storing the overall results. The easiest example is to use this to sum up all the elements in a number array: ```javascript let nums = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]; console.log(nums.reduce((sum, ele) => sum + ele), 0); // Will return 15 ``` You can do more complicated logic with multi-line arrow function. You just need to return the result as the accumulator for the next function call. ##### Array.isArray You can check if an object is an array by using this function to check whether the parameter passed is an array or not. This is needed because `typeof` doesn't distinguish between `object` and `array`. # Iterables ### Iterables A generalization of arrays, it allows us to make any object iterable in the context of `for ... of` loop. Making an object iterable just requires you to add the `Symbol.iterator` hidden property which is a function that returns the iterator. Really doubt this is ever need to be done, but the option is there if it is needed. The code for it isn't that bad. ##### String is iterable You can iterate over each letter of a String using `for ... of` loop since the String type probably have `Symbol.iterator` implemented. ```javascript for (let char of "Testing") { console.log(char); // T, e, s, t, i, n, g } ``` # Map and set, weakmap and weakset ### Map Very similar to an object, however, with object the only key that is allowed is a String. Map on the other hand allows keys of any type. Any type as it ANY type, even an object can be used as a key - `new Map()`: Creates a new empty map - `map.set(key, value)`: Sets the key-value pair into the map - `map.get(key)`: Returns the value by the `key`, returns `undefined` if `key` doesn't exist in map - `map.has(key)`: Returns `true` if the `key` exists, `false` otherwise - `map.delete(key)`: Removes the key-value pair by the `key` - `map.clear()`: Removes everything from the map - `map.size`: Returns the total number of key-value pair The way that `Map` compares keys is roughly the same as `===`, but `NaN` is considered to be equal to `NaN` hence, even `NaN` can be used as key as well! ##### Iteration over Map Three ways of iterating over a map 1. `map.keys()`: Returns an iterable for keys 2. `map.values()`: Returns an iterable for values 3. `map.entries()`: Returns an iterable for both key and value, this is the default for `for ... of` ```javascript let recipeMap = new Map(); recipeMap.set('cucumber', 500) .set('tomatoes', 350) .set('onion', 50); for (let vegs of recipeMap.keys()) { console.log(vegs); // cucumber, tomatoes, onion } for (let amount of recipeMap.values()) { console.log(amount); //500, 350, 50 } for (let entry of recipeMap) { console.log(entry) // [cucumber, 500], [tomatoes, 350], [onion, 50] } ``` The iteration follows the insertion order, unlike object which doesn't preserve the insertion order in iteration. ##### Map from array You can create a map from a 2D array like below: ```javascript let map = new Map([ ['1', 'str1'], [1, 'num1'], [true, true] ]) ``` ##### Map from object You can create a map from an object like below: ```javascript let obj = { name: "john", age: 30 } let map = new Map(Object.entries(obj)); ``` `Object.entries(obj)` will return a 2D array where the 1D array will be the two key-value properties. Since all of the key in object are String the key will always be a String. ##### Object from Map `Object.fromEntries` does the opposite, it will create an object from a map. All of the key from the map will be converted to a String, because keep in mind that object can only take String as it's key, nothing else. The values will be kept as the same. ```javascript let map3 = new Map(); map3.set(1, "50"); map3.set("name", "Ricky"); map3.set("2", "Ricky"); let obj = Object.fromEntries(map3); // {"1": "50", "name": "Ricky", "2": "Ricky}. ``` ### Set A set of unique values. There is no key-value pair mapping, `Set` only contains the values, and the same value may only occur once. - `new Set([iterable])`: To create a set, if the `iterable` object is provided, it creates a set from those values - `set.add(value)`: Add value to the set, and return the set itself - `set.delete(value)`: Remove the value, returns `true` if `value` existed otherwise `false` - `set.has(value)`: `true` if it contains the `value` `false` otherwise. - `set.clear()`: Removes everything from the set - `set.size`: Returns the number of elements in the set ##### Set iteration You can iterate over a set using same `for ... of` loop. 1. `set.keys()`: Return the iterable object for values 2. `set.values()`: This is the same as `set.keys()` 3. `set.entries()`: Return iterable object with entries `[value, value]` These method exists in order to be compatible with `Map` if you decide to switch from one to the other. ### WeakMap With normal `Map` the object that is mapped as the value will be kept in memory and so long as the `Map` exists, the object will exist as well. `WeakMap` on the other hand is different in handling how the garbage collection work. It doesn't prevent garbage-collection of key objects like `Map` does, hence their use cases are completely different. Here is how `WeakMap` works. ```javascript let weakmap = new WeakMap(); let obj = {}; weakmap.set(obj, "ok"); ``` First of all, `WeakMap` can only take object as the key, if you try to use a primitive like String or integer it will result in an error. Then, if the object we used as the key have no other references to that object (excluding the one from `WeakMap`) it will be removed from memory automatically. ```javascript let john = {name: "John"}; let weakmap = new WeakMap(); weakmap.set(john, "..."); john = null; // the object now lost the reference! // john is now lost from memory, because WeakMap doesn't prevent garbage collection of key objects. ``` In addition, there are limited functionality to `WeakMap`, there is no iteration, no way to get all keys or values from it. It only supports `set, get, delete, has` method like a normal map. ##### Use cases One of the use cases for `WeakMap` is for caching. The result from a function call associated with an object can be stored in a `WeakMap`, future calls on the same object can reuse the same result. Then when you want to clean up the `cache`, you can just delete the reference to the object and that result in `WeakMap` cache will be automatically removed from memory since it gets garbage collected. ### WeakSet Behaves similarly, but you can only ad objects to `WeakSet` no primitives. Again only supports `add, has, delete` no way of doing iterations. Used for a yes/no fact, say if an object is still being used somewhere else or not. The object will also be removed from the `WeakSet` once the object becomes inaccessible/unreachable. # Destructuring assignment ### Destructuring assignment A special syntax to let us unpack either array or object into different variables ##### Array destructuring ```javascript let arr = ["Ricky", "Lu"] let [firstName, lastName] = arr; console.log(firstName); // "Ricky" console.log(lastName); // "Lu" ``` The way the destructuring works is that it will assign the first element to the first variable that you gave, second element to the second variable that you gave, and so on... You can ignore elements that you don't want by not putting a variable for that particular element. For example, if you don't want to assign the second element and the fourth element of the array: ```javascript let arr = ["Ricky", "Lu", "Xin", "Wang"]; let [first, , third] = arr; console.log(first); // Ricky console.log(third); // Xin ```This kind of assignment works with any iterable, you can use it on `Set`, and `Map` since destructuring assignment is actually a syntax sugar for calling `for ... of` loops.

You can actually use any assignable on the left side, even object properties! ```javascript let user = {}; [user.name, user.surname] = ["Ricky", "Lu]; ``` ##### Swapping variable You can use destructuring assignment to swap two variable's value without using an intermediate variable ```javascript let a = 5; let b = 100; [b, a] = [a, b]; // Swaps a's value with b's value ``` ##### The rest '...' Normally, if you are destructuring say only one value out of the entire array, the rest of the values are just ignored. You can actually gather the rest of the values into a variable as well using the `...` syntax: ```javascript let [name1, name2, ...rest] = ["Ricky", "Xin", "Rek'sai", "Kai'sa"]; name1 // "Ricky" name2 // "Xin" rest // ["Rek'sai", "Kai'sa"] ``` It will fill in the named variable first, then anything that's left over will be stored into the rest variable as an array. Even if there are no items left, the rest variable will remain an empty array. The rest assignment must also be the last assignment in a destructuring statement! ##### Default values When doing destructuring assignment if you use more variable names than the number of elements in the array, the variables that aren't able to receive a value will become `undefined`. However, you can assign a default value for them if they didn't receive a value from the array. ```javascript let [firstname="Anonymous", lastname="Anonymous"] = ["Julius"]; firstname // "Julius" because firstname was able to receive a value lastname // "Anonymous" because there is no more value left for lastname ```You can also use function calls for default values. They will only be called if the variable didn't receive a value.

### Object destructuring Just like you can do array destructuring you can also destruct object, the syntax is a little bit different. ```javascript let {var1, var2} = {var1: ~, var2: ~}; ``` If the variable that you are assigning the property of the object into have the same name as the property name then you can just write the property name on the left. However, if you decide to assign the property to a different variable name say `name` property into just `nm`, then you would have to do a little bit more: ```javascript let {name: nm, height} = {name: "Ricky", height: "5.9"}; ``` You put the variable name that you are actually assigning to on the right side of the `:`, left side is the property name. You can also use default values as well! ```javascript let {name: nm, height=500} = {name: "Ricky", age: 50}; // name -> nm // height -> 500 ```The order that you put the property assigning does not matter

##### Rest pattern with object destructuring Again you can also use the rest variable to assign the rest of the property that you are not assigning directly to a variable into the `rest` variable. The `rest` variable becomes another object with those left over properties that you didn't assign directly. ```javascript let options = { title: "Menu", height: 200, width: 100 }; let {title, ...rest} = options; // titles -> "Menu" // rest -> {height: 200, width: 100} ``` ##### Gotcha if there's no `let` With array destructuring assignment you can declare the variable that you are using for the assigning before you actually do the assigning: ```javascript let item1, item2; [item1, item2] = [1]; console.log(item1, item2); // item1 -> 1, item2 -> undefined ``` However, with object destructuring you have to do a little bit more, using the same syntax it would not work! ```javascript let title, width, height; // error in this line {title, width, height} = {title: "Menu", width: 200, height: 100}; ``` This is because JavaScript treats `{...}` as a code block, thus it will try to execute it. To fix this you have to wrap the expression in parentheses: ```javascript let title, width, height; // error in this line ({title, width, height} = {title: "Menu", width: 200, height: 100}); ``` ##### Nested destructuring If the object that you are destructuring have nested object, then you can extract the nested object's property out as well. You just need to do another layer of destructuring with the same syntax: ```javascript let nested = { another: { name: "Inner me", age: 30, address: "6601231" }, name: "Outer me", age: 10 } let {another: {name: innerName, ...innerRest}, name: outerName, age: outerAge} = nested; // innerName -> Inner me // innerRest -> {age: 30, address: "6601231"} // outerName -> Outer me // outerAge -> 10 ``` ### Smart function parameters If you are going to write a function with many optional parameters, it might looks something like this: ```javascript function showMenu(title = "Untitled", width = 200, height = 100, items = []) { // ... } ``` Which doesn't look very nice, and when you are calling the function you will have to remember what is what. To help resolve this we can use destructuring assignment in the function parameter ```javascript function showMenu({title="Untitled", width=200, height=100, items=[]}) { // Body of the function // title, width, height, items all have default vlaues if you didn't specify it } // Calling showMenu showMenu({}); // With no parameter showMenu({width: 6969}); // With one optional parameter ``` Now when you are going to call the function, you provide in an object of parameters. If you don't want to provide any then you can just pass in an empty object. You can make empty object call even better by assigning a default value to the object destructuring assignment. ```javascript function showMenu({title="Untitled", width=200, height=100, items=[]} = {}) { // Body of the function // title, width, height, items all have default vlaues if you didn't specify it } // Calling showMenu showMenu(); // With no parameter showMenu({width: 6969}); // With one optional parameter ```Keep in mind that you are still allowed to have other parameter besides the object destructuring assignment

# JSON ### JSON file When you want to transport say a complicated object or an array of object to another compute using network. You cannot transport a complicated object just directly as "it is". You must serialize it which essentially turns the object into a stream of bytes, a string (since string can be represented using binary easily). Then send the stream of bytes over the wires, and the receiver can then reconstruct the object using the stream of bytes that you have sent. ##### JSON file syntax - JSON file can either be an array in which it starts with hard bracket, and it defines an array of objects in it - JSON file can also be an object directly in which it starts with soft brackets and it defines the property of the object - Each key of the object in JSON must be in quotation marks! No question! - Each key can map to another string, a float, boolean, an array, or another dictioanry - Each element in either object or array must be separated by a comma ### JSON.stringify This is the function that will translate a given object into a JSON. The resulted string is called *JSON-encoded* or *serialized object* or *marshalled object* that is ready to be send over the wire since it is a plain string of bytes. `JSON.stringify` is able to support the conversion of - Objects - Arrays - strings, numbers, boolean values, and even null Into JSON However, here are some of the excluded items that are excluded for the conversion - Object methods - Symbolic keys and values - Properties that are mapped to undefined ```javascript let user = { sayHi() { // ignored alert("Hello"); }, [Symbol("id")]: 123, // ignored something: undefined // ignored }; alert( JSON.stringify(user) ); // {} (empty object) ``` ##### Nested objects Nested objects are handled automatically by `JSON.stringify` so we don't have to worry about that! ##### Circular references `JSON.stringify` does not support circular references! It will be an error during conversion! ##### Extra parameter ```javascript JSON.stringify(value, replacer, space) ``` 1. `value`: Is the object that we are encoding 2. `replacer`: It can either be an array of property that we specifically ask to encode and ignore the rest, or it can be a mapping function. The function has to take in `function(key, value)`. The function will be called on for every `(key, value)` pair of the object and return the `replace` value that will be used for doing the encoding instead of the original. Return `undefined` if you don't want to encode a specific property. The reason why this is done to give us a finer control on how we want the `stringify` to be carried out 3. `space`: Specifies how many spaces to use for the output encoded string ##### Custom "toJSON" If an object implements it's own `toJSON` method for string conversion `JSON.stringify` will automatically call it if it is available to do the encoding. ### JSON.parse On the other hand, once you receive the JSON encoded string you would want to decode it back into an object so you can process it. You can do that with the `JSON.parse` method ```javascript let value = JSON.parse(str, [receiver]); ``` - `str`: The JSON-string to parse - `receiver`: An optional `function(key, value)` that will be called for each `(key, value)` pair and can be used to transform the value after it has been parseThere is some peculiarity with the receiver function, mainly in that it will be calling on each key and value pair, but at the last final iteration it will also called on the entire object where the key is an empty string and the value is the original object/array itself.

# Miscellaneous function topics ### Rest parameters and spread syntax How do we make a function take in an arbitrary number of arguments? Simple we use the `...` rest operator in the function header. ```javascript function sum(...args) { let sum = 0; for (let arg of args) sum += arg; return sum; } ``` When you prefix a parameter with `...` you can pass in an arbitrary number of arguments into the function and it will all be collected into an array that's stored into the parameter `args`. You can also mix rest parameters with normal parameters like so ```javascript function showName(firstName, lastName, ...extra) { console.log(firstName, lastName); console.log(extra); } showName("Ricky", "Lu", 30, 40, 50); ``` In this case, the first two parameter will be stored into `firstName` and `lastName` respectively, and any further parameter that you pass in will be stored into `extra` as an array of parameters.Keep in mind that the `rest` parameter must be at the end when you use it. You cannot have a function like so `function f(arg1, ...rest, arg2)` this will be a syntax error

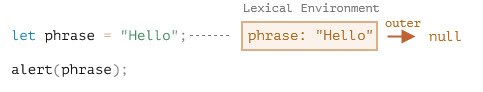

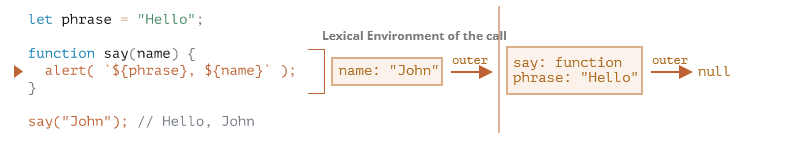

##### Spread Syntax On the other hand, you can also unpack the values from an array or any iterable into a function. For example: ```javascript // instead of writing let arr = [3, 5, 1]; console.log(Math.max(arr[0], arr[1], arr[2])); // Too long, and if there are hundreds of values, we are not gonna do this console.log(Math.max(...arr)); // Much better, this unpacks the arr ``` This is much like the opposite of doing the reverse of rest parameter. We want to spread the values from an array into the parameter of a function. When `...` is used in a function call it expands the iterable object into the list of arguments. You can spread multiple iterable into a function ```javascript let arr1 = [1]; let arr2 = [2, 3, 4, 5, 6]; function foo(a, ...rest) { console.log(a, rest); } foo(...arr1, ...ar2); // prints out "1 [2, 3, 4, 5, 6]" ``` ##### Merging array You can also use the spread syntax to merge arrays together, instead of using `arr.concat` ```javascript let arr = [3, 5, 1]; let arr2 = [8, 9, 15]; let merged = [...arr, ...arr2]; // becomes [3, 5, 1, 8, 9, 15]; ``` ### Lexical environment Okay this is gonna just be a brief summary of what lexical environment is. Every JavaScript script have something called a lexical environment object that is internal. It consists of: **Environment record** (all of the local variables and methods), and a **reference** to the outer lexical environment. When you declare a global variable or global function it is stored in the global lexical environment that is associated with the whole script. [](https://wiki.tamarine.me/uploads/images/gallery/2022-12/image.png) Here in this example above, `phrase` is a global variable and hence its record is stored in the global lexical environment. The global lexical environment does not have reference to a outer lexical environment because it is the most outer one, hence it is just `null`. ##### Variable declaration and function declaration When you declare a variable, it is available in the lexical environment immediately but the value it has is uninitialized from the beginning, and as the script execute to the point where it is initialize, that value is updated. On the other hand, for function declaration (not function expression or arrow functions), they are available immediately become ready-to-use functions. It doesn't have to wait until the line the function becomes defined to be initialized. This is why we are able to call the function before the function declaration! ##### Inner and outer lexical environment When you invoke a function it creates a new lexical environment to store the local variables and parameter of the function call. **Every new function invocation will create a new lexical environment!** [](https://wiki.tamarine.me/uploads/images/gallery/2022-12/hrGimage.png) Here in this example, invoking `say` creates a new lexical environment and has the parameter information in it. It has the reference to the outer lexical environment, which in this case is the global lexical environment. **When the function wants to access a variable, the inner lexical environment is searched first, then the outer one, and recursively back up until the global lexical environment.** If the variable is not found anywhere, then it is an error in `strict mode`, without `strict mode` then assignment to a non-existing variable will be automatically added to the global lexical environment. ##### Returning a function If you wrote a function that returns another function say: ```javascript function makeCounter() { let count = 0; return function() { return ++count; }; } let counter = makeCounter(); counter(); // count becomes 1 counter(); // count becomes 2 ``` In this case `makeCounter()` creates a lexical environment that holds the variable `count`, then it returned a function that will increment the outer `count`. How does it do that? When `counter` is invoked later on, it will again create a new lexical environment with nothing in it because it has no variables but rather referring to the outer one. Since it is created in the lexical environment in `makeCounter` the reference that the inner function points to will be `makeCounter`'s lexical environment and it has the `count`. Then when it tries to increment `count` it will be incrementing the `count` under `makecounter`'s lexical environment and it works out! ##### Closure Now this is where closure comes in. A closure is a function that is able to remember it's environment context that it was created in. It remembers the outer variable and is able to access them. Some languages don't support closure, and if it doesn't then what we have just talked about isn't possible. All JavaScript functions are closure, is able to resolve those outer variables that it used, and when those variables goes out of scope it is still able to remember them, have closure per say. The only exception is the `new Function` syntax, it is not closure. ### Global object The global object provides variables and functions that are available anywhere, by default it stores the ones that are built into the language or the runtime environment. For browsers it is named `window`, for Node.js it is `global`, but it is recently been renamed into `globalThis` You can access the property of global object directly. In addition, all `var` variables are becomes the property of the global object. Variables without `let` or `var` are implicitly `var` hence they become the property of the global object as well! (Without strict mode that is. With strict mode, it is an error) ##### Usage of global variable It is generally discouraged, there should be as few global variables as possible, with access via the global object that is. ### The `new Function` syntax You can create a new function via a string: ```javascript let func = new Function([arg1, arg2, ...argN], functionBody); // Both the args and functions should be strings ``` For example: ```javascript let sum = new Function('a', 'b', 'return a + b'); let sum = new Function('a, b', 'return a + b'); // Both are equivalent. sum(1, 2) // will be 3 ``` Now using this way to create function it is not closure. Meaning that it cannot access any outer variables! This is the only exception that functions aren't closure, in all other cases functions in JavaScript are closure. ### Named function expression When you are writing a function expression you don't normally give it a name, but the thing is you can, so writing this is perfectly valid: ```javascript let sayHi() = function func(who) { console.log(`Hi ${who}`); }; sayHi("John"); // Hi John ``` But what does this achieve? By adding a name to the function expression it did not become a function declaration, it is still a function expression! You can still call the function as it is using `sayHi`. However, by adding `func` name we are able to let the function calls itself internally, and it is not visible outside of the function. ```javascript let sayHi = function func(who) { if (!who) { func("Anonymous"); } else { console.log(`Hi ${who}`); } } sayHi(); // Hello, guest! ``` We use `func` internally instead of `sayHi` is because the value of `sayHi` could be changed down the line, and if it is changed, to say a number, then the reference inside would not be valid anymore. ```javascript let sayHi = function(who) { if (who) { alert(`Hello, ${who}`); } else { sayHi("Guest"); // Error: sayHi is not a function } }; let welcome = sayHi; sayHi = null; welcome(); // Error, the nested sayHi call doesn't work any more! ``` ### Scheduling ##### setTimeout/setInterval Both follows the function header: ```javascript setTimeout/setInterval(func | code, [delay], [arg1], [arg2], ...) ``` - `func`: Refers to the function to execute - `delay`: The number of milliseconds to wait before the code specified is executed, by default is 0 so execute immediately. - `arg1, arg2,...`: The arguments for the function that you specified ```javascript function waveHello() { console.log("I am waving hello!") } setTimeout(waveHello, 1000); // I am waving hello! After one second ``` The difference between `setTimeout` and `setInterval` is that `setTimeout` will only execute the function once after the specified delay, while `setInterval` will execute that function regularly after every specified `delay`. So if you write `setInterval(waveHello, 1000)` this will wave hello after every second. ##### clearTimeout/clearInterval Use these two functions to delete the function that is going to be called after you do `setTimeout/setInterval`. You will have to pass the "timer identifier" that is returned from calling `setTimeout/setinterval`, in order to cancel the timer handler. ##### Nested setTimeout A better way of doing interval code execution is via nested `setTimeout` ```javascript setTimeout(function tick() { console.log("Doing work every regularly"); setTimeout(tick, 2000); }, 2000); ``` Recalling from named function expression that an function expression can be named and itself can refer to it internally. Now the first function execution will occur after 2 seconds, then it will run the body of the `tick` function, it will do the work and schedule itself to run 2 seconds again later. Why is this better? It gives us a finer control on when to schedule, instead doing it every 2 seconds, we can control the time of the interval inside the `tick` function based on say CPU-usage, or how much work is given. We can do it every 10 seconds, 20 seconds, or 60 seconds so a variable interval is what this is trying to emulate. In addition, nested `setTimeout` guarantees the fixed delay. Since `setInterval` the function execution can take up the delay, thus making the interval inaccurate. ##### Zero delay setTimeout There is actual a usage for `setTimeout(func, 0)`. This schedules the execution of the function as soon as possible, but the scheduler is invoked only after the current executing script is complete. Hence the function is scheduled to run right after the current script is finished. ```javascript setTimeout(() => console.log("World"))console.log("hello!");// Prints out hello! World ``` ### Function binding If you decide to somehow pass an object's method as a callback into say `setTimeout`, you will lose the `this` keyword in the method ```javascript let user = { firstName: "John", sayHi() { console.log("Hi I am " + this.firstName); } }; setTimeout(user.sayHi, 1000); // This will print Hi I am undefined ``` The method that was passed into `setTimeout` didn't have a receiver when it was invoked. So again if the method that you invoked doesn't have a receiver, in browser `this` will be binded to `window` object, and for Node.js it will be the `timer` object, but not that relevant. ##### Solution 1: Wrapper We can solve this by wrapping the method that we actually want to invoke in another function call like so ```javascript let user = { firstName: "John", sayHi() { console.log("Hi I am " + this.firstName); } }; setTimeout(function() { user.sayHi() }, 1000); // This will print Hi I am undefined ``` Now because of closure, it is able to resolve `this` to be the appropriate user object and this will be fine. However, this solution will fail if the `user` object somehow changed before the callback is executed, then it will be invoked on the changed value, not the old one anymore. ##### Solution 2: bind To solve the issue that was discussed previously where if the object is somehow changed before the callback is executed, it will be executing callback with the updated object, we can use the `bind` function to fix this. ```javascript let boundFunc = func.bind(context); ``` The result of calling `bind` on a function is another function that has the same body but with `this=context` fixed. For example: ```javascript let user = { firstName: "John" }; function func() { console.log(this.firstName); } let funcUser = func.bind(user); funcUser(); // John, because this is set to be user. ``` The returned function will have the same spec as the original function the only thing that changed is that `this` is fixed to whatever object that you have provided. Using `bind` we can solve the problem we have just discussed by fixing the `this` to be that original object, it won't matter if the object changed down the line: ```javascript let user = { firstName: "John", sayHi() { console.log(`Hello, ${this.firstName}!`); } }; let sayHi = user.sayHi.bind(user); // (*) // You can run it without an explicit receiver sayHi(); // Hello, John setTimeout(sayHi, 1000); // Hello, John // Even if user is changed to something else, it will still do Hello, John user = {}; ```After you have bind an object, it cannot be changed again! Meaning you cannot do .bind again on the function that was returned.

##### Partial functions With the `bind` method you can also fulfill the partial parameter, here is an example ```javascript function mul(a, b) { return a * b; } let double = mul.bind(null, 2); double(3) // 6 double(8) // 16 ``` We can partially fill out the function that we are binding with some predetermined parameter, in this case `a=2`, then the user only need to fill out one more parameter `b` in this case and the result will be returned. You can also make methods that are partial as well if you so to choose, this is done by using the `func.call` method which invokes the method with the option to provide the `this` context. Then you can just return a function that will call the method with the predetermined parameters, and let the user provide additional parameter. ```javascript function partial(func, ...argsBound) { return function(...args) { // Returns a function that is partially filled. Let user put in additional args if needed return func.call(this, ...argsBound, ...args); } } let user = { firstName: "John", say(time, phrase) { alert(`[${time}] ${this.firstName}: ${phrase}!`); } }; // add a partial method with fixed time // takes in the function to partially fill, and the args to prefill with user.sayNow = partial(user.say, new Date().getHours() + ':' + new Date().getMinutes()); // user.sayNow is a prefilled method, it this is binded to the same user object still // because func.call(this...) // now you can call the function with any additional method that was needed after prefilled user.sayNow("Hello"); ``` # Getters & setters ### Virtual property In addition to the normal property that we have for objects, we can also set up virtual properties. They appears to the outside code as if they were the object's property but they are actually implemented as functions underneath. ```javascript let user = { name: "John", last: "Smith", get fullName() { return this.name + " " + this.last; } set fullName(value) { [this.name, this.last] = value.split(" "); } }; console.log(user.fullName); // John Smith user.fullName = "Ricky Lu" console.log(user.fullName); // Ricky Lu ``` Like mentioned before to the outside, `fullName` looks like a property but underneath it is implemented as an method. There is getter that uses the `get` keyword before the function name to provide a virtual attribute that you can read from, and there is `set` keyword to provide a setter that you can assign the virtual attribute.For an object there is two type of property, an accessor property which is a virtual property that has either `get/set (or both)` method, or a data property that is just the normal property which we have been dealing with.

### Property flags and descriptors For each property that an object has besides the value it contains it also have some additional metadata. Namely, they are called property flags - `writable`: If `true`, the value can be changed, otherwise it's read-only. If you attempt to assign to non-writable property then error will only show up in strict mode - `enumerable`: If `true`, the value will be listed in loops, otherwise it is not listed - `configurable`: If `true`, the property can be deleted and these attributes can be modified, otherwise, it cannot be deleted or modified anymore. If this flag is set the only flag changing operation that is permitted afterward is to turn `writable` to be `true -> false` to add another layer of protection - `value`: Describes the value of the property ##### Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor(obj, propertyName) You can use this method to get the property descriptor of a specific property to see which property flag is set and which one isn't ##### Object.defineProperty(obj, propertyName, descriptor) You can use this method to set a specific property's property flag, if it is defined in the object then it will just update the flag, otherwise, if the property doesn't exist then it will create the property with the given value and flags. If the flags aren't supplied it is assumed to be all `false`. ##### Object.defineProperties You can define many properties at once instead of just one at a time # All about prototypes ### Prototype inheritance Every object have a special hidden property `[[Prototype]]` it is either `null` or a reference to another object. Whenever you read a property from `object` and if it is missing, JavaScript will automatically take it from the prototype. ##### Setting prototype One of the way to set the prototype is to use the special name `__proto__`: ```javascript let animal = { eat: true }; let rabbit = { jump: true }; rabbit.__proto__ = animal; console.log(rabbit.eat); // true, taken from the prototype animal console.log(rabbit.jump); // true ``` If `animal` has any useful method, then since it is a prototype to the `rabbit` it is able to call it directly as well! ```javascript let animal = { eats: true, walk() { console.log("Walking"); } }; let rabbit = { jumps: true, __proto__: animal // Another way of setting the prototype }; // walk is taken from the prototype rabbit.walk(); // Walking ``` ##### Limitation The only rules on assigning prototype is that there should be no circular references, and the value of `__proto__` should be either an object or `null` all other types are simply ignored and have no effect. ##### Modifying prototype state What if we did something like this? ```javascript let user = { name: "Ricky" last: "Lu" get fullName() { return this.name + " " + this.last; } set fullName(value) { [this.name, this.last] = value.split(" "); } }; let admin = { __proto__: user, isAdmin: true }; console.log(admin.fullName); // Ricky Lu, this works as expected admin.fullName = "Another person"; // Now what happens to user.name and user.last? admin.fullName // Another perons user.fullName // Ricky Lu, it stays! The state of user is protected ```As you can see if you tried to modify the admin's name by calling the prototype's setter function the state change will be enforced on `admin` and not `user`! Even though you are calling `user`'s setter method. This is because `this` always binds to the object that it is called on, and in this case, it is assigning `admin.name` and `admin.last` to be `"Another"` and `"person"` respectively. `user` is unchanged.

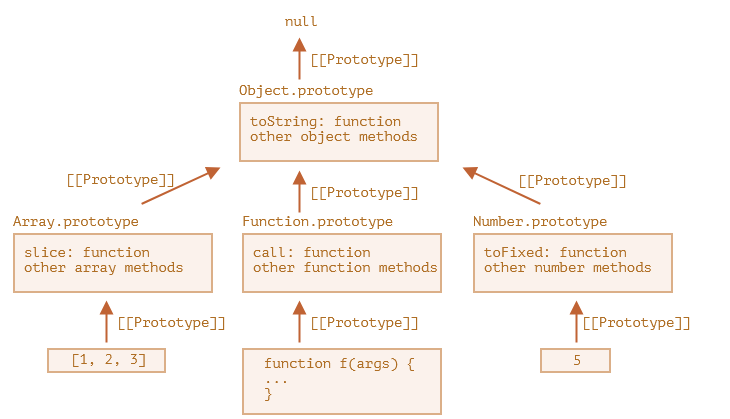

Even if you do something like this: ```javascript let user = { name: "Ricky" last: "Lu" }; let admin = {}; admin.name = "Another"; admin.last = "person"; user -> Will still be "Ricky Lu" admin -> Will be "Another person", because it is assigning name and last property to admin ``` This behavior is needed because you wouldn't want to modify the prototype's state if multiple object has it as it's prototype, the changes will be untraceable and should be on the object itself not prototype! ##### for...in loop Using `for...in` it will iterate over the inherited properties as well if it is enumerable, however, `Object.keys(obj)` will only return the keys this object has itself, not inherited ones: ```javascript let animal = { eats: true }; let rabbit = { jumps: true, __proto__: animal }; // Object.keys only returns own keys console.log(Object.keys(rabbit)); // jumps // for..in loops over both own and inherited keys for(let prop in rabbit) console.log(prop); // jumps, then eats ``` ### Native prototypes These are the built-in prototypes that all of the objects inherits from. ##### Object.prototype This is the default prototype that any object created inherits from. And itself's prototype is just `null` because there is no one above it. This object has some default method that all object contains `toString, hasOwnProperty,...` ##### hasOwnProperty(prop) Return `true/false` depending on whether or not the object has that particular property itself, and not inherited. ##### Array.prototype/Function.prototype/Number.prototype These are the other prototypes that some of the objects that you create inherits from such as Arrays, Functions, and Numbers. You can verify that they indeed are those prototype by comparing say `[1, 2].__proto__ == Array.prototype` it will be equal to `true`. [](https://wiki.tamarine.me/uploads/images/gallery/2022-12/T2simage.png) ##### Primitives Primitives aren't objects, but somehow we are able to access methods on them, how does that work? Well when you try to access their methods a temporary wrapper objects are created using the built-in constructors `String, Number, Boolean`. They provide the methods and then disappear. The process of creation are invisible to us and engines optimize them out mostly. `null` and `undefined` have no object wrapper, so they have no methods or properties.One of the interesting thing that you can do with primitive prototypes is that you can add some custom properties or method that can be used by all primitives. `String.prototype.foo = 5;` will allow all strings to access a foo property. `let x = 5;` you can do `x.foo` to get 5.

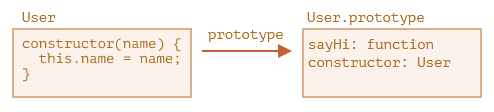

### Interesting aside If you set a property to an object and marked it as `enumerable: false`, and you `console.log` the object, that property will not show up because it is not iterated over using `for...in` loop! ### F.prototype When writing constructor functions, i.e. functions that are called with `new F()`, where `F` is a constructor function we can take advantage and use `F.prototype` to do prototype inheritance as well. If we assigned an object to `F.prototype` then when `new F()` is invoked, the object that is created will have its `__prototype__` pointed to the object that we have assigned. So it is another way that we can do prototype inheritance, instead of setting it manually after the object is created using `{...}`. ```javascript let animal = { eat: true }; function Rabbit(name) { this.name = name; } Rabbit.prototype = animal; let rabbit = new Rabbit("White"); // rabbit.__proto__ == animal console.log(rabbit.eat); // true ```Keep in mind that `F.prototype` is only used when `new F()` is called, so if you decide to change it prototype after you created the object, future object created using the constructor function will have the newer prototype, but existing object keep the old one.